This is the second of two posts considering the rewards and challenges of using DSLRs for cinema work. If you've not read the first post, start there.

At the end of the last post we had assembled a Canon 7D camera, a Canon 17-55 f/2.8 lens with Image Stabilizer, a Zoom H4N audio recorder, and PluralEyes software to help us sync the picture and sound in Final Cut Pro. The cost: $3230. I hesitate to call this a "bare bones" package since it doesn't even include a tripod or microphones. It does, however, get you picture and sound.

But you get picture and sound with a pixelvision camera. My intention with these posts is to compare DSLRs to a more traditional prosumer camcorder. And we still have a ways to go before it's a fair comparison. So let's continue...

For starters, the Sony and Panasonic cameras have ND filters built into their cameras. And while there may be some optional kit with the Canon DSLR rigs, ND is not one of them. Not, at least, if you want that creamy shallow DoF cinema look, which is probably the reason you bought the Canon in the first place.

Some people, including Philip Bloom, swear by the FaderND, which cuts out between 2 and 8 stops of light. If you find it on Ebay you'll pay around $125. Very cool!

Others, though, argue that the FaderND can make color correction a problem later on. Indeed, the quality of your lens is reduced if you put inexpensive glass in front of it. (Or, as Shane Hurlbut warns, "beware the reaper of cheap glass"!) So if you do want to be careful, you would need to budget between $275 and $450 for a set of high quality Tiffen "Water White" IR ND filters.

If you've got multiple lenses with different filter ring sizes you'll need to purchase step-down rings. But for now, we're assuming we only have one lens.

Let's throw caution to the wind and go with the Fader ND. That puts us at $3355.

We also need to power the camera and record to something. So we need some CF cards and we need some batteries.

We would obviously need batteries if were were going with a more all-in-one solution (i.e., an actual video camera) like Sony or Panasonic. But in my experience the batteries supplied by these manufacturers last about 2x as long as those supplied by Canon, in part because the Canons weren't really built for, you know, constant video footage. And, a manufacturer like Sony or Panasonic supplies an AC adapter so you can run your camera off wall power. Canon does no such thing. So to be fair, we'll add the cost of two batteries ($156), even though you'll actually need four or five to shoot a day's worth of footage.

($156), even though you'll actually need four or five to shoot a day's worth of footage.

As far as CF cards are concerned, for a starter package, we'll figure you need 32GB of CF memory. That's about $77 . Hurlbut makes a compelling argument that you should use lots of 8GB cards instead, but we'll stick with one card, which gives you about the same recording time as the 16GB SxS card that comes supplied with the Sony Ex1R (roughly an 1 hour).

. Hurlbut makes a compelling argument that you should use lots of 8GB cards instead, but we'll stick with one card, which gives you about the same recording time as the 16GB SxS card that comes supplied with the Sony Ex1R (roughly an 1 hour).

What are we up to now? $3588.

Finally, in my experience, I've found you need some sort of way to monitor your footage. The on camera LCD focusing system is not large enough to accurately focus on the fly. And it is often impossible to use in broad daylight.

The focusing issue is, for some, a real deal breaker, and for good reason: Everyone I know that has used this camera has shot footage that appeared to be in focus but, upon later inspection on an actual monitor, learned that the take was a bust. You have to be very careful about monitoring your footage, and you need to check every shot on a large monitor (Hurlbut recommends a 24" LCD) before you move on to the next setup.

I'm not going to include the cost of the 24" LCD. We're going bare bones here. So we're going to use a Zacuto Z-Finder ($395), which magnifies the camera's LCD viewfinder.

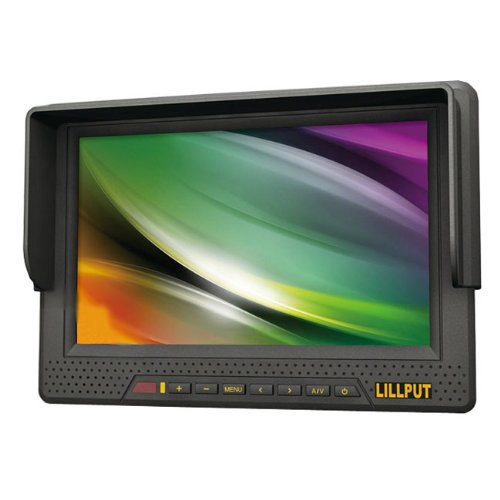

Another option is to use an external monitor while shooting. The advantage is, obviously, a larger viewing area to judge focus. The disadvantage is that once you add an external monitor (with battery pack, HDMI cable, and hardware) you lose the small, stealthy DSLR form-factor. Good monitors are expensive, too, often averaging around $800-$1000. The cheapest possible monitor option, however, gives the Zacuto Z-finder a run for its money. That monitor is the Lilliput 669GL.

The Lilliput is only $220, but you'll need a battery solution. I recommend the Ikan 107S or P ($68) depending on whether you already might have some Sony or Panasonic batteries. And you'll need a special MiniHDMI-to-HDMI cable ($12). And you'll need an arm (Ikan's MA206 is the cheapest somewhat decent solution at $70) to mount the monitor to your camera.

The total cost of the Lilliput option as I've described it is around $350. If you need Sony or Panasonic batteries to power it (and a charger to charge the batteries) then your total will exceed that of the Z-finder. So let's just add $395 for the Z-finder and be done with it.

By the way, I've not been tallying shipping costs on these items, but lots of places like Amazon, B+H, and Adorama offer free shipping on certain items, so you might get lucky.

I think this does it for a bare bones kit. Remember, my estimates do not include the things you'll need to actually shoot for an entire day -- things like extra batteries, multiple CF cards, a camera bag or case(s), a shoulder mount, or a tripod. Nor does it include things like quick release plates for your tripod and shoulder mount. Nor does it include any sort of rod system or a follow focus, which you may want since the whole purpose behind using these cameras is to have that all-important shallow depth of field.

The final total? $3983.

That's twelve dollars cheaper than Panasonic's HPX-170.

So the question is, which do you want?

Traditional low-level professional camcorder:

- not a stills camera

- less cinematic depth of field

- fixed lens

- somewhat video-ish handling of light

+ actual HD resolution

+ accurate focusing

+ less pronounced jell-o problems

+ single-system sound with XLR inputs

+/- all in one build (pros: it's meant to be used this way; cons: looks like a video camera)

+ solid HD codec

+ stability/durability as a camera intended for video

Canon DSLR:

+ great stills camera

+ cinematic shallow depth of field

+ option of interchangeable lenses

+ beautiful handling of light

- difficult-to-edit codec with "reversal film" (i.e., limited) flexibility

- less-than-HD resolution

- issues obtaining accurate focus

- aliasing and moiré problems

- jell-o problems

- double system sound with separate sound recorder

+/- modular build (pros: pick what you need; cons: you're only a strong as your weakest link)

- some overheating problems*

* Did I mention that there have been some issues with overheating since video on these DSLR's is so demanding? If the camera overheats, it may not work for a while. One solution is to have another camera body on hand (+ $1700).

***

Look, I'm not advocating one camera over another. And I am not trying to diss on the DSLR revolution. I'm just trying to cut through the hype to talk realistically about the choices that exist for a low-budget filmmaker.

Cameras -- like life, art, and love -- are full of compromises. The question is, what are the compromises you can deal with, and what are the deal breakers?

Just how badly do you want that bokeh?

Are you willing to sacrifice reliability?

Are you willing to risk losing half a day's worth of work?

Are you willing to endure slow-downs because you have to re-shoot footage?

If so, how much?

I don't have the answers. At the beginning of this series I said I was ambivalent. And I meant it. I haven't made up my mind about these cameras. I doubt I will. It will be a case-by-case, project-by-project thing.

I think there will be some times where these cameras are appropriate for me to use. They're great for clandestine filming. I like them for filming in/with/around cars. I like the way they handle close-ups. If I was single-handedly making a shot-for-shot remake of The Passion of Joan of Arc, this would be my camera. (Hmm…)

But if I had to choose only one camera to own, a DSLR would probably not be it. I won't even consider it for documentary, or documentary style, filming because of the shallow focus and overheating issues, never mind the moire and jello.

Do I think DSLRs are game-changing technology? Only sorta. These cameras have been handicapped by the corporation that produces them. Whether intentionally or not, it doesn't matter. Either way, it's the same old corporate routine. Call it the corporate camera cha-cha: One step forward, one step back. What has people intrigued about DSLRs is that the steps forward and back are not the ones we're used to.

With time maybe I'll come around to love these cameras whole-heartedly, but even if that happens I will not argue that DSLRs have "democratized" filmmaking in any meaningful way:

First, as I think I've demonstrated, at their current price point these cameras aren't that much cheaper than other things on the market. When we talk about "democratized technology" we must be talking, on one level, about cost. And on this score, they do not pass the test. (The T2i makes a somewhat better case, but it's also the most handicapped of the bunch.)

Secondly, DSLRs -- as they are currently designed -- actually require more know-how to use effectively than other cameras that can be used for filmmaking. In this sense, DSLRs are actually less "democratic" than other existing movie-making technologies.

Finally, even if -- especially if -- I allow that these DSLRs are getting more people to make movies, let me address a bigger point:

"Democratized" technology serves little purpose if it isn't being used in the service of stories that otherwise couldn't be told. Otherwise, what's the point of democratizing it?

Put another way, if you have the means to make a movie, and you only use that technology (not to mention your time and talent) to make another frigging zombie movie, well, pardon me for not caring. If the storytelling is out of focus, who cares how beautiful the bokeh is?

In 2010 I

In 2010 I

,

,  , and a

, and a  . The Canon and Nikon were each impressive in their own ways, but I gave them both up because I could never fully trust the image that I saw in their LCDs. After being burned a few times by outrageous moire that only appeared once I could view footage on a real monitor, I gave up trying to shoot with those cameras.

The GH1, which I tested last summer after my frustrations with the Canon cameras, was more promising, especially with the ballyhooed firmware hack that surfaced last year. That camera didn't have problems with moire or aliasing, and its mirrorless design (the GH1 is not, technically speaking a DSLR at all) opened up the opportunity for using several different types of lenses (PL-mount cine lenses, Nikons, Canons, and many more).

. The Canon and Nikon were each impressive in their own ways, but I gave them both up because I could never fully trust the image that I saw in their LCDs. After being burned a few times by outrageous moire that only appeared once I could view footage on a real monitor, I gave up trying to shoot with those cameras.

The GH1, which I tested last summer after my frustrations with the Canon cameras, was more promising, especially with the ballyhooed firmware hack that surfaced last year. That camera didn't have problems with moire or aliasing, and its mirrorless design (the GH1 is not, technically speaking a DSLR at all) opened up the opportunity for using several different types of lenses (PL-mount cine lenses, Nikons, Canons, and many more).

, shortly after they arrived in the US. A month or so later, here are my thoughts on the camera as a tool for filmmakers.

, shortly after they arrived in the US. A month or so later, here are my thoughts on the camera as a tool for filmmakers.  strap, which screws into the camera's base.

strap, which screws into the camera's base. !), but they require a 4/3-to-Micro4/3 adapter. Probably the sexiest native lens for the camera is Voigtlander's super fast 25mm f/0.95. Regardless of which of these you choose, you're spending from anywhere near $1000 to $2500 for a lens that won't work on either of the other major camera systems (e.g., Nikon or Canon). If the next great camera that comes down the road isn't a Micro 4/3 system camera, but something with a larger sensor (and this is considerably likely) an investment in M43 glass may not repay long term dividends. That said, there is a solid work-around solution. More on this later...

!), but they require a 4/3-to-Micro4/3 adapter. Probably the sexiest native lens for the camera is Voigtlander's super fast 25mm f/0.95. Regardless of which of these you choose, you're spending from anywhere near $1000 to $2500 for a lens that won't work on either of the other major camera systems (e.g., Nikon or Canon). If the next great camera that comes down the road isn't a Micro 4/3 system camera, but something with a larger sensor (and this is considerably likely) an investment in M43 glass may not repay long term dividends. That said, there is a solid work-around solution. More on this later... adapter. You can even get an adapter for Nikon

adapter. You can even get an adapter for Nikon  (i.e., lenses without an aperture ring), which would be most useful with something like a Tokina 11-16 f/2.8 lens. Users of Canon glass are limited to something like a Kipon adapter, which fakes an aperture, only somewhat successfully. The great thing about Nikon glass is that it's usable on Canon cameras, too, as well as, of course, Nikons. Should either of those manufacturers step up and invent the next great HDSLR, you won't miss a beat.

(i.e., lenses without an aperture ring), which would be most useful with something like a Tokina 11-16 f/2.8 lens. Users of Canon glass are limited to something like a Kipon adapter, which fakes an aperture, only somewhat successfully. The great thing about Nikon glass is that it's usable on Canon cameras, too, as well as, of course, Nikons. Should either of those manufacturers step up and invent the next great HDSLR, you won't miss a beat. ($156), even though you'll actually need four or five to shoot a day's worth of footage.

($156), even though you'll actually need four or five to shoot a day's worth of footage. . Hurlbut makes a

. Hurlbut makes a

at the bottom and the

at the bottom and the  and

and  at the top. The 7D averages around $1700. That sounds like a bargain when you put it next to a traditional prosumer camcorder like the Sony EX-1R ($6300) or the

at the top. The 7D averages around $1700. That sounds like a bargain when you put it next to a traditional prosumer camcorder like the Sony EX-1R ($6300) or the  ($3995).

($3995). . It's been

. It's been  ), those are additional costs.

), those are additional costs. [$70 each] to use them effectively. Plus, when you want to use your Canon DSLR as a stills camera, you'll have no autofocus or auto exposure control, so I'm leaving them out of the conversation for now.)

[$70 each] to use them effectively. Plus, when you want to use your Canon DSLR as a stills camera, you'll have no autofocus or auto exposure control, so I'm leaving them out of the conversation for now.) recorder. It's about $280. (If I were buying, I'd spend the extra $250 and get the

recorder. It's about $280. (If I were buying, I'd spend the extra $250 and get the  because it's easier to use. But that's just me.) An alternative is to use something like a Beachtek or JuicedLink adapter, but I don't like the idea of all my location sound hinging on a single mini plug going into something that was primarily designed as a stills camera.

because it's easier to use. But that's just me.) An alternative is to use something like a Beachtek or JuicedLink adapter, but I don't like the idea of all my location sound hinging on a single mini plug going into something that was primarily designed as a stills camera.